Interview: Moroccan poetess Niama Benhallam

12 November, 2017

Moroccan poetess Niama Benhallam to "Sudanow":

- Moroccan and Sudanese people have a long-established relationship rooted in history.

- Asilah city commemorated Tayeb Salih by naming him on one of the gardens of the city. His masterpiece “The Season of Migration to the North” is taught in the Moroccan universities.

- Elfitory had a project, a vision and a mission. He was the leader of African dimensioned poetry in Africa and in the Arab world.

- Mohamed Bennis is one of the greatest modernist poets in Morocco.

- Without translation, we would not have enjoyed Al-Khayyam’s masterpieces.

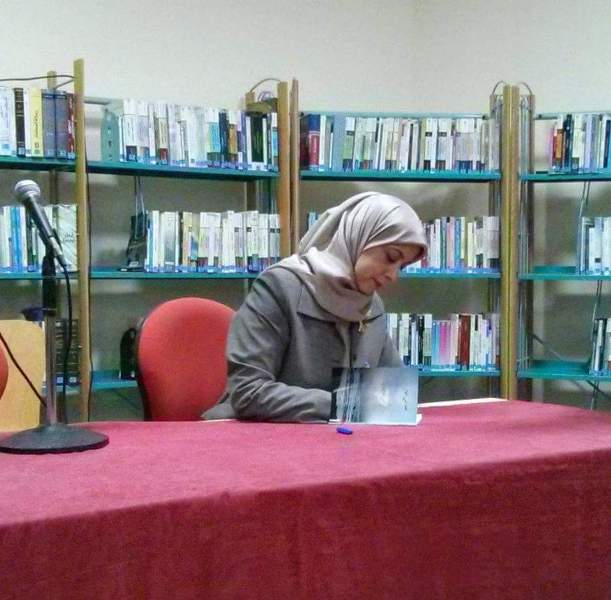

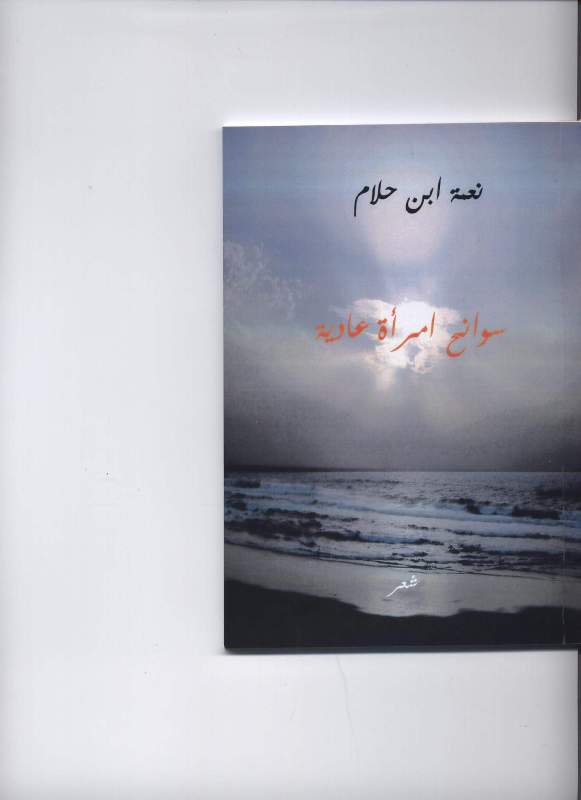

KHARTOUM (Sudanow) - Poetess Niama Benhallam is one of the new distinguished voices in Morocco. She has many contributions in translation. She translated from French into Arabic a number of poems of eminent French poets such as Victor Hugo, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Charles Baudelaire, as well as from English into Arabic, mainly some short sonatas of Shakespeare. She also translated from Arabic into French a number of poems for Moroccan poets. Currently, she is heading a public library in Meknes. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in library sciences from the ‘School of Information Sciences’ in Rabat, a Bachelor’s degree in English studies from Moulay Ismail University in Meknes, and a Master's degree in English studies from the same university. She participated in local, national and Arab poetry meetings. She published her first collection of poetry entitled “Sawanih Imra’ah Aadiyyah”.

In this phone interview “Sudanow” discussed with her many Arab and Moroccan cultural issues.

Sudanow: The title of your poetry collection "Sawanih Imra’ah Aadiyyah” is equivocal, what is the message behind it?

Niama: Three words may need many pages to find out their profound implication, and still, stay open to all possibilities of interpretation. However, I will refer to some entries for each item. I intentionally chose 'Sawanih' which means thoughts that come to someone’s mind instead of 'poetry', just to give the receiver the opportunity to judge my writings by him/herself; the active reader and the professional critic are to decide the poetics of what they read. ‘Imra’ah’, a woman, used with indefinite article can be understood as if I voiced women and their sufferings in general. ‘Aadiyyah’ is a polysemic word. Among its several meanings: 1- the racer, as cited in the holy Qura’n “By the racers, panting” (Al-Aadiyyat, 1) the racers refer to the horses or the camels according to the Qur’an interpreters. Life is effectively like a battlefield where everybody runs. 2- ‘Aadiy’ means someone who transgressed due limits. Allah (swt) says “But if one is forced by necessity without willful disobedience or transgressing due limits, then there is no sin on him.” (Al-Baqarah, 173). Then the word is perhaps used in reference to being unjust; and I was unjust, but only towards myself. 3- ‘Aadiyy’ means also ordinary, simple and not exceeding the common people. Undoubtedly, the word in this sense is used to provoke the reader and to invite him/her to read this ordinary woman, bearing in mind the cultural, social and civilizational dimensions of the word, and as Foucault presents what is normal and what is insane, and how madness is seductive because it is knowledge. Generally, one cannot understand the choice of the word ‘Aadiyyah’ unless they read the last words of the last text in the collection and which is entitled "Madness", and try to understand why this rotation and why I finished by what came in the beginning.

Q: What is the situation of Moroccan poetry within the Arab creativity map?

A: Moroccan poetry has been present in the Arab creativity map since the last century and there are prominent names who were able to emerge in the poetic scene on the national, Arab and international scales, for instance, Abdel Karim Tabbal, Mohamed Bennis, Mohamed El Halwi, Malika Assimi, Amina El-Mrini, Wafaa El Amrani, to name but a few. In recent years there has been a considerable accumulation of new publications and many new names have emerged. However, quantity is not a valid indicator to make sure that what is published is real poetry. Time only will sieve out and keep all that is good while the rest will evaporate.

Q: How do you see the relationship between criticism and new writers in Morocco?

A: There are many publications and many names, but academic criticism is almost absent, and here I refer to the role of the university that should direct students in their research to the field of literary criticism, thus giving the opportunity to the new writers to be read and to criticism as an inevitable movement to stand on all new writings, and evaluate them according to criticism norms.

Q: The effects of Moroccan cultural reality on poetry and writing.

A: Poetry and writing influence and are influenced by time, space and context. Culture, civilization, history, as well as societal, political, intellectual and economic changes are all factors that sharpen visions, melt experiences and raise self-awareness and societal awareness. Hence, the will to express the anxieties connected with this awareness emerges and evolves till it becomes a psychological need to create a textual structure that responds to all these elements and offers a writing that articulates self-endurance or the wounds of the nation in its local, Arab, and universal dimensions. Moroccan poetry passed through different stages, and its concept changed according to the context. In the late 19th century, it was mere verses composed in the classical way of the Arab poem, and concerned with jurisprudence, grammar and rhetoric; and serving as a tool to easily memorize these sciences. In the early 20th century it became relatively independent. In the 1930s, there was a sharp struggle between the pros and cons of renewal, but the interaction between Morocco and the East at this time played an important role in the development of Moroccan poetry and the evolution of its structure and content. In the 1940s, romantic poetry emerged, and young poets and critics emerged too. Some of them supported romanticism and some of them advocated realism. In the 1970s, the question of modernity emerged and the modernist poem broke out in all its forms.

Q: You write vertical poetry and free verse poetry. How do you read Mohamed Bennis and prose poetry?

A: Mohamed Bennis, one of the greatest modernist poets in Morocco, writes in total freedom. He mixes types and goes beyond traditional structures. He emphasizes that it is only the degree of involvement in writing that can make the difference between poetry and prose. As for me, I also wrote a few prose texts that did not exceed three or four. What I write with love, or rather what writes me because the poem comes suddenly at that moment when you are not waiting for it, is the free verse poetry. It provides me with gratification, amazement, and this delightful sense of musicality. But what is poetry essentially? Isn’t it that flow of emotions that converts blood into ink that draws the hidden torments of the soul? If the text has flying images that offer magic and wonderment, if it is written in transparent and pure language reflecting the transparency of the poet, and engendering poetic and internal music that makes you feel comfortable reading and rereading it, then there no harm if it is not measured or rhymed. This is my opinion, but it does not imply that I may write prose poetry in the future.

Q: Critics often say that translation is a transgression of the translated poem. Is this true or is it mere exaggeration?

A: Without translation, we would not have enjoyed Al-Khayyam’s masterpieces for instance, we would not have savoured poetry written in languages that we do not know, and others would have known nothing about our poetry. Therefore, translation is a necessity and not a luxury; it is the bridge between cultures and literary arts. Poetry translation specifically has always raised lot of controversy between those who believe that poetry is lost in translation and those who see that the beauty of some translated poems may equal the original text if not exceed it. From my perspective, poetry translation is a complex and gratifying process at the same time. It provides a pleasure that does not exist in writing, the admiration of a poem may generate the desire to own it and create it again, but because it is impossible to do so, writing it in another language may relieve the translator. What is to be observed is to preserve the essence of the original text. The mastery of both languages is not enough to translate poetry, it must be felt, enjoyed and to blend it with the soul and the heart so that it can be born again in a poetic language no less beautiful than the original. Poetry translator, I dare say, must be a poet so that the translated poem is not emptied from its essence.

Q: Moroccan identity and its dialectics between a purely national Moroccan identity and an Arab Islamic identity and Francophone identity as a gateway to the world.

A: It is not possible to talk about Moroccan identity without mentioning that Morocco, by virtue of its geographical situation, its history and the succession of civilizations on it, and the fusion of Amazigh and Arabs coming from the East and then from Andalusia after being melt with the European component, produced a human being who inherited a rich legacy in which the amazigh culture interacted with the Arab with the Saharian with the Andalusian ones. Moroccan people are rich in their diversity, in their cultures, their Arab and Amazigh languages, their Islam and their openness to the West; and the Moroccan identity is all of these elements combined and there is no room for talking about a purely Moroccan national identity or Arab Islamic identity. As for the Francophone, it recalls the traces of colonialism such as language and the cultural background connected to it. If we consider the Francophone from the post-colonial discourse, I will evoke Homi Bhabha who says in his work “Nation and Narration” that after colonial periods, the system of culture of any formerly colonised nation will necessarily be ambivalent and hybridized. Thus, the new dominant culture cannot leave and its traces cannot be erased. Its mark remains present even after a long time. At the same time, it is incontestable that language is the container of thought and openness to other languages is openness to different cultures, civilizations and ways of thinking. Such openness is enriching insofar as the person is not lost between two languages, two cultures, contradictory identities, and not to fall into the trap of Francophone politics which is only a form of colonial globalization.

Q: Qatar's cultural role in preserving Arab identity and heritage starting with the Doha Magazine and the Katara Award, which has become a gateway for many Arab authors.

A: Qatar plays a pivotal cultural role at the Arab level as it strives to promote culture and creativity in all their forms and aims to build bridges of constructive communication between Arab cultures from East to West. Since the 1970s, Doha magazine has taken care of Arab culture. Despite some delay, it resumed its activities welcoming several prominent Arab and foreign writers; it joined to the issues a monthly book and a quarterly translated book. Qatar has also been keen to sponsor major cultural projects such as the Katara Award, which promotes and encourages talents, thus contributing to the raise of cultural and cognitive awareness and serving the Arab societies that aspire to a better cultural level.

Q: Sudanese poet Mohamed Elfitory settled in Morocco, died and was buried there. How did he influence Arabic poetry, and how did Moroccan intellectuals read him?

A: It is difficult to talk about a great poet such as the late Mohamed Elfitory and how he affected Arabic poetry in some few short lines. He is the poet of Africa by excellence. He is the free conscience that voiced Africa in Arabic. He wrote about the tragedy of the "person of color" and his history burdened with slavery and struggle for freedom. He wrote about Arab and African leaders such as Mandela, Lumumba, Nkrumah and Ben Bella. The late Elfitory had a project, a vision and a mission. Africa was a major theme in his poetry. He was the leader of African dimensioned poetry in Africa and the Arab world. Concerning how Moroccan intellectuals read Elfitory, I will refer mainly to the critical work of Moroccan critic Benaissa Bouhmala "The tendency of Negritude in Contemporary Poetry: Mohamed Elfitory as a case study" (Alnaz’aa Alzinjiya Fi Chchi’r Almu’asir: Mohammed Elfitory Namuzajane) published in two parts by the Union of Moroccan Writers. This book evokes negritude as a “theme” on which Elfitory worked as a mean of resistance to colonial hegemony, the latter produced three successive poetry collections about Africa and the black man: Aghani Ifriqiya (The Songs of Africa), Ashiq meen Afriqia (Lover from Africa), Ozkor'inni Yaa Afriqia (Remember Me Africa). It is noteworthy that the name of the continent is repeated in the three collections to confirm the Afro-Sudanese identity of the poet, and it is perhaps the Arab component of his identity that made him settle in Rabat in Morocco till his death. Morocco, in return, received him warmly, celebrated, and honored him during his life and after his death. Other Moroccan Critics also read Elfitory and shed light upon his exceptional poetic characteristics. Poet and critic Salah Bussrif considers Elfitory one of the innovators who refined the Arabic language and enabled it to voice itself and not to be just the echo of another voice. The academic and professor of semiotics Saïd Benkrad also sees that Elfitory has maintained the Arab cultural conscience in the continent of Africa, while critic Mohamed Bakri considers Elfitory’s poetic experience, that has broken the white and black dichotomy, one of the richest experiences in the movement of modern poetry. At the academic level, many doctoral dissertations about his poetic experience were presented in Moroccan universities; and he is included in undergraduate studies and in secondary school curricula.

Q: Tayeb Salih had a good relationship with Asilah. Why did he love Morocco?

A: Tayeb Salih loved Morocco and Morocco loved him. He loved Asilah and used to attend its annual festival organized by the Asilah Forum Foundation under the presidency of the former Moroccan Minister of Culture Mohamed Benaissa. He participated in the festival since 1980 to 2006 when his disease prevented him from travelling. In return, Asilah city commemorated him by naming him on one of the gardens of the city in a ceremony attended by a group of Moroccan, Sudanese and Arab intellectuals. In 2002, he won the Mohamed Zafzaf Prize for Arabic Novel, offered by the Asilah Forum Foundation. Tayeb was also professor at the Moroccan University. His masterpiece “The Season of Migration to the North” is taught in our university. He is famous and if he had written only that novel, it would have been enough to offer him fame and appreciation.

Q: Sudanese scholar Professor Abdullah al-Tayeb was an authority in Moroccan history and was a participant in the lessons Hassania. What do you think?

A: This is sure; professor Abdullah al-Tayeb was a professor at the University of Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdallah in Fez, Morocco. He took part in the lessons Hassania in the presence of the late King Hassan II, who used to invite to these lessons eminent Arab and foreign Muslim scholars. In my point of view, Moroccan and Sudanese people in general have a long-established relationship rooted in history through the Sufi orders that were established in Morocco and reached Sudan, and Moroccan scholars who went to Sudan, married and settled there. Hence, there is blood that unites us. It is no wonder, then, that we love Sudan and that Sudan loves us. We are one family since early times.

E N D

AS

Comment

Khalid AMAR

08 July, 2018I am proud of my dear student Neama Benhallam

Gazi saiful Islam

03 October, 2019Nice interview article, I like it. I want to translate it in Bengali, Bangladesh. Thanks all